August 2025

Yasu Taniwaki

Chairman, Digital Policy Forum Japan (DPFJ)

In December 2024, the DPFJ released a policy agenda titled “Digital Policy After the Change of Government 1 ” (priority issues to be considered as future digital policy). This agenda characterized 2024 as “a crucial year in which more than 60 countries held national elections, with over half of the world’s population choosing politicians as their representatives.” It noted that the main issue in these elections, as pointed out in the G20 Leaders’ Declaration (November 2024)2, was “how to change the situation in which domestic and international inequalities lie at the root of the global challenges we face, and where those very challenges exacerbate inequality.” Addressing this theme of “correcting distributive inequality” has also become a major issue in digital policy.

Accordingly, this paper reviews the direction and content of digital policy in the first half of 2025, following the results of national elections, from the perspective of digital policy (specifically digital governance, including data governance, AI governance, and security governance), while also surveying changes in relations among major countries accompanying changes of government.

Data Governance — Institutional Development Underway

(Trends in private organizations)

In October 2024, the DPFJ published a proposal titled “Promoting Data Governance” (a joint proposal by three organizations, including the DSA (Data Society Alliance) and JDTF (Japan Digital Trust Forum), hereafter referred to as the “DPFJ Proposal”). This proposal outlined a direction to maximize the use of data as a strategic intangible asset, advance the resolution of social issues and the creation of added value, and promote institutional development to realize regional revitalization, new industry creation, and enhanced economic security.

Similarly, Keidanren (Japan Business Federation) published two proposals, “Toward Building an Industrial Data Space” (October 2024)3 and “Second Proposal Toward Building an Industrial Data Space” (May 2025)4 , which recommended the establishment of a public-private council to promote the construction of data spaces and related initiatives.

(Trends in government and ruling party)

In light of these private-sector developments, in May 20255 the Liberal Democratic Party’s Digital Society Promotion Headquarters published “Digital Nippon 2025.” This document recognized that “in today’s world, where data is the source of value creation, the construction of flexible and efficient data linkage systems that contribute to solving social issues and creating new businesses is essential for all industries and public services.” As concrete promotion items, it listed:

- • Construction of a cross-sectoral data linkage platform

- • Strengthening of the function as the command center of the Digital Agency

- • Acceleration of industrial data space development

- • Development of comprehensive legal systems for promoting data linkage (including trust-related legislation)

This clarified a stance of promoting data governance centered on data spaces.

In June 2025, following this, the government’s Digital Administrative and Fiscal Reform Council adopted the “Basic Policy on the Data Utilization System.”6 This basic policy included:

- • Consideration of a drastic revision of the Basic Act on Promotion of Public-Private Data Utilization for developing a common infrastructure (digital public infrastructure7 ) for data linkage (to be submitted to the next regular Diet session)

- • Development of infrastructure related to trust services

- • Promotion of international standardization, including data formats

As a result, public and private sectors came into alignment in promoting data utilization. To implement this direction concretely, it was announced in June 2025 that a new Public-Private Council on Digital Ecosystems8 would be established, chaired by the Digital Agency and Keidanren. This council will also include the three organizations including the DPFJ, and is expected to begin full-scale activities in autumn of this year.

Related Institutional Developments in the Transition to a Data-Driven Society

(Revision of GDP Statistics)

First, regarding the shift toward a data-driven society, there is a growing awareness of the problem that the impact of the data economy on the overall economy cannot yet be sufficiently analyzed. To address this, moves have emerged toward revising economic statistics.

Specifically, in March 2025, the UN Statistical Commission adopted the 2025 SNA (new GDP standards)9 . The key point is the “valuation and capitalization of data.”

This means that data, as an intangible asset, would be recorded as an asset in economic statistics. By clarifying the economic value of data, it becomes possible to indicate its importance as a strategic asset in monetary terms. At present, however, estimates of data value are limited to cost-based calculations. In the future, through the construction of data spaces and the development of data distribution markets, market-based valuation of data is also expected to progress. Such initiatives may even lead to the recognition of data as assets in corporate financial accounting.

Incidentally, countries aim to introduce GDP statistics compliant with the new standards by 2029–2030, so it will be necessary to continue monitoring these developments.

(Ongoing Review of Competition Law)

Next, the DPFJ Proposal noted that “one of the main issues in recent national elections has been correcting income distribution, and in the midst of a trend toward stronger protectionist tendencies to shield domestic markets, we must closely monitor developments so that countries’ digital policies move toward promoting the free cross-border flow of data.”

In other words, as the weight of intangible assets such as data increases, it will be necessary to build corrective measures into the social system to address monopolization of data by a small number of businesses, from the perspective of “correcting distributive inequality” mentioned earlier. Data, as an asset, tends to generate market oligopolies due to its characteristics of “zero marginal cost” stemming from extreme economies of scale, and its non-rivalrous nature. This makes it easier for monopolistic structures to emerge. Therefore, the strengthening of competition law—such as large-scale platform regulations targeting GAFA in Europe and Japan—must be continually reviewed and revised to maintain effectiveness, given the rapid pace of market structural change.

(Debates over Digital Democracy)

Furthermore, from the perspective of preventing the concentration of data, it is also necessary to reconsider traditional systems of political participation and democracy, including electoral systems in the digital age, as needed. At the same time, discussions should be deepened on new forms of digital democracy utilizing digital technologies10.

AI Governance — Emerging New Divisions

(The validity of an AI law based on non-regulation)

Next, concerning the approach to AI governance, the DPFJ Proposal, based on the separately developed “Toward Building an AI Governance Framework (ver. 2.0)” (December 2025)11, identified three basic perspectives: minimizing AI risks, establishing an environment to maximize the benefits of AI, and creating markets to realize such an environment as autonomously as possible. Concretely, it emphasized the importance of promoting:

- • Enactment of a Basic AI Law centered on minimal regulation and voluntary risk management

- • Active use of AI in wide-ranging fields such as education and healthcare

- • Formulation of a comprehensive strategy for creating new industries centered on AI

Among these, regarding the enactment of an AI law, the “Act on the Promotion of Research, Development and Utilization of Artificial Intelligence-Related Technologies” was promulgated and enforced in June 2025 (with some parts to be enforced on dates set by Cabinet orders within three months of promulgation)12.

This AI Law stipulates the establishment of an AI Strategy Headquarters and the formulation of a Basic AI Plan, while avoiding the application of direct regulation on AI. It thus took the form of a basic law that clearly articulated a fundamental stance of “non-regulation of AI,” in line with the spirit of the DPFJ Proposal13.

The government, based on this AI Law, plans to proceed with the formulation of the Basic AI Plan and the development of AI guidelines. It remains to be seen whether the above-mentioned “active use of AI” and “formulation of a comprehensive strategy for new industry creation” will advance. In particular, given that in Japan even guidelines tend to carry quasi-legal moral force, care must be taken to ensure that the government does not intervene excessively in AI risk assessment. At the same time, it is necessary to establish the environment to ensure that access to AI is provided on a non-discriminatory basis.

(The Inauguration of the New U.S. Administration and Emerging AI Conflicts)

Looking at the trends of major countries in AI governance, a new axis of confrontation is becoming evident. Traditionally, China established “Generative AI Regulations” that effectively excluded foreign generative AI (by prohibiting such AI from producing content banned under Chinese laws and regulations). In contrast, former Western nations assumed that AI should be freely accessible to everyone, and it was thought that the differences between authoritarian states and liberal states would sharpen further within the field of AI governance.

However, since the inauguration of the Trump administration in the U.S. in January 2025, serious conflicts have begun to arise even within the Western bloc. In February 2025, at the AI Action Summit held in France, a declaration was adopted that included ensuring that AI is “open, inclusive, transparent, ethical, safe, secure, and trustworthy (while taking international frameworks14 into account).” Sixty-four countries and regions, including Japan, signed this declaration. EU Commission President von der Leyen stated, “People need confidence that AI is safe. This is the very purpose of the AI Act.”

In contrast, the U.S. refused to sign this declaration15. Vice President Vance declared: “Excessive regulation of the AI sector could kill an innovative industry still in its takeoff stage. We will dedicate ourselves fully to growth-oriented AI policy.” Thus, a conflict has emerged between Europe, which seeks to ensure user trust in AI through hard law such as the AI Act, and the U.S., which argues that AI, as a technology still under development, should grow further under a non-regulatory approach.

(Challenges Facing U.S. AI Policy)

In January 2025, the U.S. issued a new presidential order that entirely repudiated the Biden administration’s AI policies. Under Biden, the October 2023 Presidential Order on AI Governance had avoided direct regulation but promoted soft-law approaches: setting NIST standards for Red Teaming to detect AI vulnerabilities, and developing explicit guidance to prohibit algorithmic discrimination. All these policies, however, were scrapped with the change of administration.

Instead, in July 2025, the Trump administration announced a new presidential order on AI and an AI Action Plan.

The AI Action Plan outlined three pillars (a total of 30 items):

- • Accelerating AI innovation

- • Promoting the construction of U.S. AI infrastructure (including development of the power grid and reshoring semiconductor manufacturing)

- • Leading in international diplomacy and security concerning AI

This reconfirmed traditional positions such as reviewing regulations that hinder AI. It also included items with a strong unilateral U.S.-centric character, such as promoting exports of U.S. AI to allied nations and urging allies to follow U.S. restrictions on AI and semiconductor exports to China.

Additionally, the federal government announced a policy of “ideological neutrality” — meaning that LLMs biased toward ideologies such as DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) would not be procured by federal agencies. As many commentators have noted, while the Chinese approach involves state intervention in the content of AI-generated outputs, and the U.S. approach involves intervention under the name of “ideological neutrality,” both represent state interference (government reach) into AI. This raises serious concerns about violations of freedom of expression, a core value of liberal democracies.

The DPFJ Proposal had warned: “As government involvement in cyberspace grows stronger, there is concern that confrontation between liberal states and authoritarian states will sharpen further in AI governance.” In reality, however, confrontation has also arisen between Europe and the U.S. over regulatory approaches to AI, while China and the U.S. now exhibit similarities in their interventions into AI outputs. This creates an increasingly complex structure that warrants close attention going forward.

Security Governance — Building a Comprehensive Deterrence Strategy

In cyberspace, the boundaries between peacetime and wartime no longer exist, and situations such as gray-zone incidents and hybrid warfare (where civilian and military uses merge) have already become a reality. Accordingly, in everyday socio-economic activities, careful attention must be paid to cyberattacks that may involve state actors or reflect state-level conflicts.

(Significant Progress in Active Cyber Defense)

Against this backdrop, the Act on Strengthening Cyber Response Capabilities passed in May 202516 represents a major step forward in strengthening Japan’s cybersecurity system. Legal arrangements for active cyber defense, which were first clearly presented in the National Security Strategy approved by Cabinet in December 202217, have now been institutionalized. The key points of this new law include:

- • Strengthening public-private cooperation: while various initiatives had been underway previously, the new law reinforces requirements such as incident reporting by critical infrastructure operators, establishing a new public-private council for information sharing (with participation from computer vendors as well as infrastructure operators), and government-to-private sharing of vulnerability information on computers.

- • Institutionalizing active cyber defense: measures include establishing an independent body to balance the use of communications data with the secrecy of communications. In July 2025, this led to the reorganization and strengthening of the NISC (National Center of Incident Readiness and Strategy for Cybersecurity), resulting in the establishment of the National Cybersecurity Office (NCO).

(Toward Building a Comprehensive Cyber Deterrence Strategy)

Going forward, it will be necessary to build a comprehensive cyber deterrence strategy and, on that basis, strengthen international cyber cooperation among like-minded nations. Such a deterrence strategy must effectively combine two forms of deterrence18:

- • Deterrence by Punishment — discouraging adversaries by threatening to impose costs exceeding the benefits they would gain from their actions.

- • Deterrence by Denial — persuading adversaries that their actions will be futile and ineffective.

Additionally, it will be necessary to promote private-sector security investment (for example, encouraging the perception of cybersecurity expenditures as investments rather than costs by improving corporate disclosures, and introducing tax incentives for capital investment).

To address the severe shortage of cybersecurity personnel, new initiatives must also be pursued. These include establishing training facilities funded by government subsidies but primarily operated by the private sector, and setting up new public-private talent development centers that operate cyber ranges utilizing government and private-sector incident data.

(Institutional Development for Responding to Cognitive Warfare)

In building a cybersecurity strategy, it is essential to secure the three elements of data: confidentiality, integrity, and availability.

Ensuring data integrity, in particular, is becoming extremely important for the realization of a data-driven society. For example, in recent election campaigns, there have been instances of bot attacks suspected of involving state actors. Attacks targeting election systems — the very foundation of democracy — (i.e., cognitive warfare) could become even more severe. Countermeasures, including those against disinformation during peacetime, are thus necessary.

In this regard, the National Security Strategy stated that the government would “establish a new structure within the government to strengthen response capabilities in the cognitive domain, including dealing with the spread of disinformation.” There is therefore an urgent need to set up a government department dedicated to handling cognitive warfare.

Multipolar International Cooperation — The Increasing Complexity of Digital Diplomacy

(Divergent National Visions of Digital Policy)

Countries do not share a uniform basic direction in digital policy. Here, let us summarize the digital policies of four major powers/regions: the U.S., Europe, China, and India.

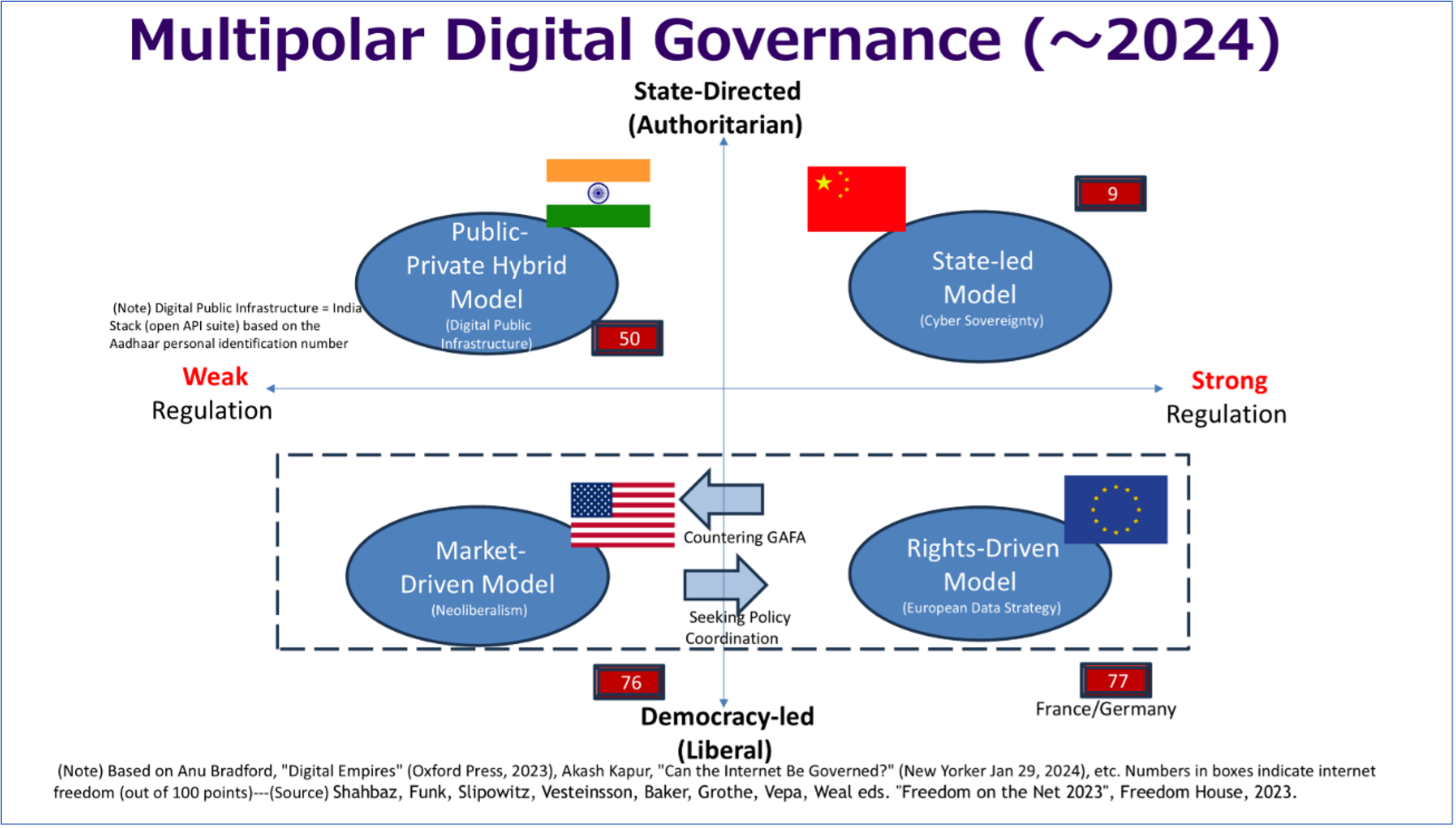

(Fig1)

(Fig1)As shown in Figure 1, if the horizontal axis represents the “strength of regulation” (with greater regulation toward the right) and the vertical axis represents the “degree of state involvement” (with authoritarian state-led approaches at the top and liberal citizen-led approaches at the bottom), we can see four distinct models of digital states19.

- • The United States: Traditionally adopts a “market-driven model” centered on neoliberalism, respecting market mechanisms to the maximum. Under the Biden administration, countermeasures against the market dominance of platform operators such as GAFA (through antitrust enforcement) were a major issue for competition authorities. However, with the transition to the Trump administration, these initiatives disappeared entirely, and the U.S. clarified a stance of prioritizing market mechanisms domestically while unilaterally pursuing its own interests internationally. This has left WTO and other multilateral rules for cross-border trade in goods and services dysfunctional, creating extreme uncertainty for the future.

- • Europe: In its European Data Strategy (February 2020)20, the EU pointed out that “in a society where individuals continuously generate data, the collection and use of data must be conducted in accordance with European values, fundamental rights, and rules.” Thus, it has adopted a “rights-driven model” based on protecting European citizens’ rights. The GDPR is a prime example, ensuring strict protection of personal data within the EU while also applying extraterritorially, imposing fines and penalties for violations by entities outside the EU. This framework strongly reflects Europe’s countermeasures against GAFA. In addition, Europe has aggressively pursued a comprehensive legal framework — from the Digital Services Act (DSA) for user protection, the Digital Markets Act (DMA) for platform regulation, and the Data Act for promoting data distribution, to the AI Act. This has created the so-called “Brussels Effect” by spreading its influence globally.

- • China: Until the early 2000s, its focus was on industrial policy such as nurturing the domestic digital industry. From the 2010s, however, it began advocating “cyber sovereignty,” strengthening internet censorship, introducing the social credit system, and enacting the “Data Laws Trilogy21” including restrictions on cross-border data transfers. This reinforced its state-led model. In August 2024, China formulated the “Five-Year Plan for Building Data Spaces” following the publication of the “20 Measures on Data” (December 2022), the establishment of the National Data Bureau (March 2023), and the “Action Plan for the Development of Trusted Data Spaces (2024–2028)” (November 2024), which aims to build over 100 data spaces by 2028.

- • India: Unlike the U.S., Europe, and China, India represents a “public-private partnership model.” Here, the government develops digital public infrastructure and makes it broadly available to the private sector to expand the digital services market. The foundation is Aadhaar, a 12-digit individual identification number linked to basic personal information and biometric data (iris, fingerprints, facial photo). On this basis, open API groups called the “India Stack” provide services such as electronic KYC, eSign, real-time interbank transfers (UPI=Unified Payments Interface), and personal storage (DigiLocker). These APIs are made freely available to private businesses. By providing digital public infrastructure (platforms) as a public good and ensuring fair access, India seeks to avoid data monopolies by large platforms and foster a wide range of citizen-driven digital services. The “India Stack” has rapidly spread to the Global South, adopted recently in countries such as the Philippines and the UAE. It has proven effective in promoting financial inclusion (online lending, small remittances, fair subsidy distribution), aligning well with the needs of the Global South. Thus, this model is likely to form a “fourth pole,” potentially intensifying competition with China’s “Digital Silk Road” initiative.

(Changing Models of Digital States)

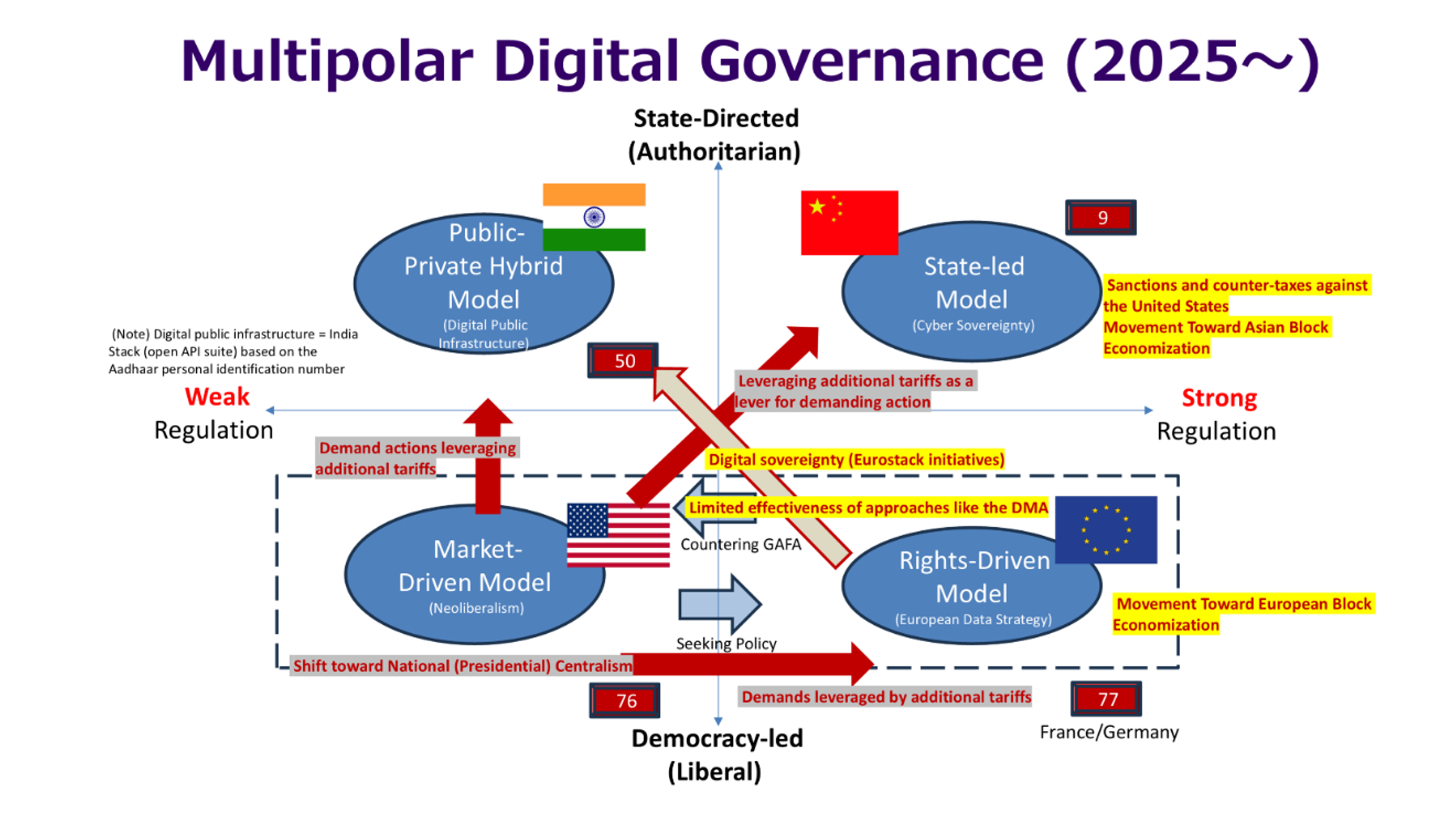

How will the four digital state models described above (U.S., Europe, China, and India) evolve going forward? (See Figure 2).

(Fig 2)

(Fig 2)Once again, the policies of the Trump administration in the U.S., such as additional tariffs and other unilateral measures, have had a major impact. The U.S. has imposed numerous demands on trading partners, often criticized as lacking rational justification, using additional tariffs as leverage. This pursuit of “America First” has created rifts with virtually all of its partners to varying degrees. In response, China has imposed retaliatory tariffs on the U.S. and sought to strengthen its economic partnerships with ASEAN countries by leveraging its negative stance toward the U.S.

Europe, meanwhile, has taken countermeasures against GAFA through a series of digital-related laws and regulations. However, these have not produced sufficient results, and perceptions have spread that European citizens’ data remain locked in GAFA’s walled gardens. Against this backdrop, the Draghi Report22 published in September 2024 stated that Europe’s digital lag is the main cause of its productivity gap with the U.S., pointing to shortcomings such as insufficient innovation ecosystems in the digital sector and the dispersal of digital infrastructure investment leading to weak impact. The report stressed that Europe must aim to create and disseminate its own digital technologies in order to regain digital sovereignty. These ideas have quickly gained traction within Europe, partly in reaction to pressure from U.S. tariffs. The Eurostack initiative, which now includes about 100 companies including Airbus, seeks to secure Europe’s independent digital sovereignty.

(Japan’s Position as a Digital State)

Amid these developments, where does Japan stand? Looking at its strategies for digital technology development and competition policy, Japan’s orientation is relatively close to that of Europe. For example, the joint statement of the Japan–EU Regular Summit in July 2025 included the following:

- • Expanding cooperation under the Digital Partnership in areas such as data governance, AI, and online platforms

- • Continuing cooperation on data governance, including data spaces, to strengthen “Data Free Flow with Trust (DFFT)”

Japan may also pursue a direction similar to India’s, where the government builds public digital platforms (infrastructure) and opens their APIs, enabling diverse private-sector application models — a form of public-private partnership model.

In any case, the central issue in digital policy discussions is how to secure digital sovereignty. Particularly, as national digital policy directions evolve, not only are differences becoming evident between liberal states (U.S., Europe, Japan) and authoritarian states (China, Russia, etc.), but cracks are also emerging within the liberal bloc itself, notably between the U.S. and Europe. In this sense, countries are increasingly aiming for their own unique forms of digital sovereignty.

Digital sovereignty must be discussed from two perspectives: data sovereignty, which involves maintaining control over a nation’s own data, and technological sovereignty, which ensures independent controllability over a nation’s digital infrastructure. Debates over digital sovereignty must go beyond technology, deepening discussions from diverse perspectives including the economy, diplomacy, security, and culture.

Conclusion

In the areas of digital governance — including data governance, AI governance, and security governance — this paper has reviewed key policy trends in the first half of 2025.

From a broad perspective, it can be understood that countries’ digital policies are generally moving in the direction envisioned in the DPFJ Proposal. At the same time, digital technologies such as AI are evolving at a pace beyond expectations, and with the advent of the Trump administration, divergences in digital policy among countries, including allies, have become more pronounced. This reinforces the importance of continuing comprehensive examinations of digital policy trends across nations, as undertaken in this paper, on a regular basis.

2 https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/100755776.pdf

3 https://www.keidanren.or.jp/en/policy/2024/073_proposal.pdf

4 https://www.keidanren.or.jp/policy/2025/026_honbun.pdf (※Japanese only, same below)

5 https://storage2.jimin.jp/pdf/news/policy/210615_2.pdf (※)

6 https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/seisaku/digital_gyozaikaikaku/pdf/data_houshin_honbun.pdf (※)

7 The Digital Administrative and Fiscal Reform Conference’s “Basic Policy on Data Utilization Systems” (June

8 https://www.ipa.go.jp/jdep/ (※)

9 https://www.esri.cao.go.jp/jp/sna/seibi/2025sna/2025sna.html (※)

10 See, for example, Audrey Tang & E. Glen Weyl “PLURALITY: The Future of Collaborative Technology and Democracy”. https://www.plurality.net/

12 https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/outline/168/905R744.pdf (※)

13 The DPFJ proposal also recommended taking the form of “basic law” similar to the Cybersecurity Basic Act. Some arguments emphasize “no penalty provisions,” but what’s really important is that “the law contains no regulations that restrict citizens’ rights and obligations when using AI.”

15 Among major countries, the UK also didn’t sign the declaration. But unlike the US, the UK’s reason for not signing was reported as “concerns about national security and international AI governance.”

16 https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/seisaku/cyber_anzen_hosyo_torikumi/index.html (※)

17 https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/siryou/221216anzenhoshou/nss-e.pdf

18 Deterrence strategies include diplomatic condemnation, economic sanctions, and international legal prosecution as punitive deterrence, while denial deterrence includes active cyber defense and other ways to neutralize opponent attack capabilities beforehand.

19 The US, China, and Europe models are based on “Digital Empires” (Oxford Press 2023) by Anu Bradford. For India’s digital public infrastructure, see Akash Kapur “Can the Internet Be Governed?” (New Yorker, Jan. 29, 2024).

20 European Commission “A European Strategy for Data” (Feb. 2020) https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0066

21 “Data Laws Trilogy” refers to the “Cybersecurity Law” (effective June 2017), “Data Security Law” (effective July 2021), and “Personal Information Protection Law” (effective November 2021).

22 Mitsubishi Research Institute (MRI) “Overview of the Draghi Report and Implications for Japan” (October 2024) https://www.mri.co.jp/knowledge/insight/dep/2024/i5inlu000000zz0x-att/dep20241029.pdf